React

On July 12, 2024, around noon, I (Anan Striker) had an appointment with my living source, Gijs. We met in a place in Amsterdam whose name already has something letter-like: the fourth letter, in capitals, of Gijs's graffiti name 'REACT' - Capital C.

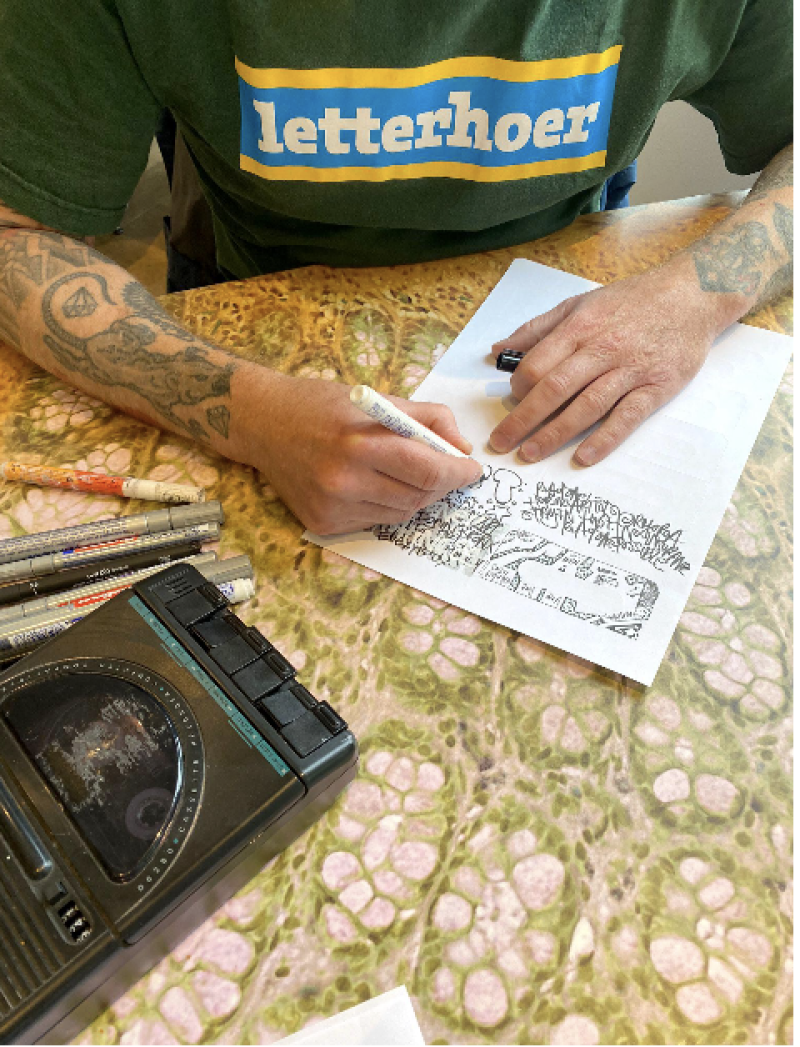

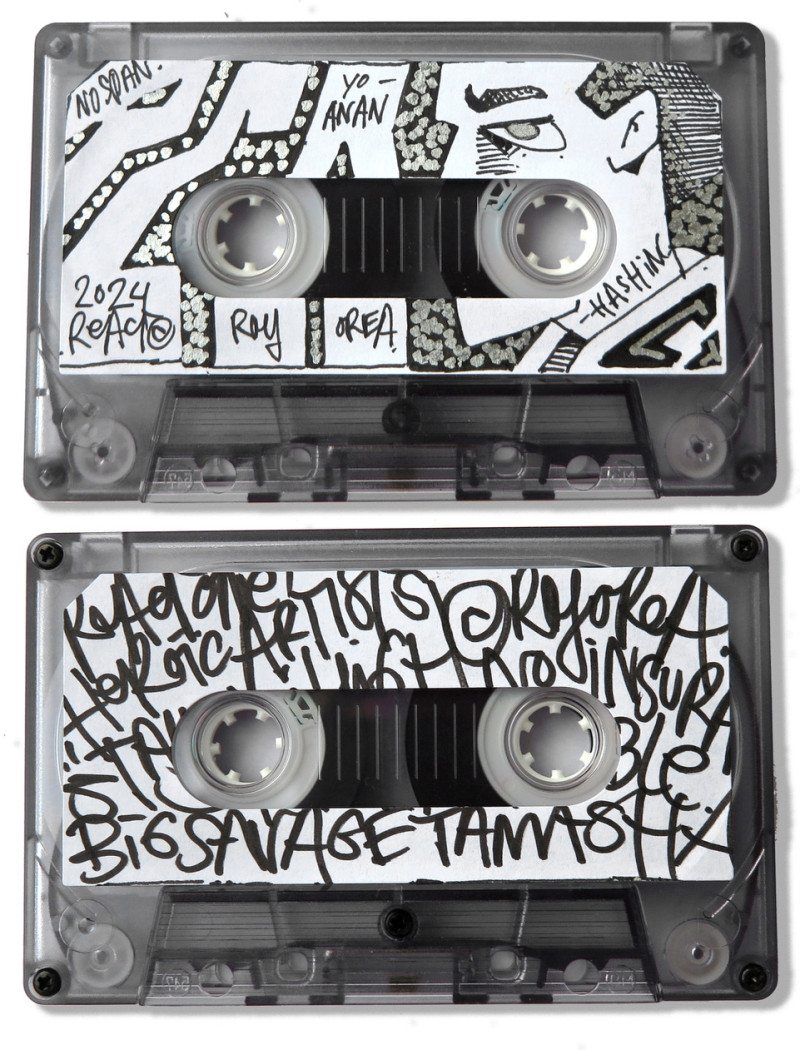

It was a rainy day and I cycled with healthy excitement through the drizzle to our appointment. I didn’t really know what to expect. Will he be an enthusiastic storyteller? Will my questions be adequate enough? Will we “click”? Upon entering, I saw someone with the words “letter whore” on his shirt. That must be REACT! He made a gesture of recognition and I walked up to him. After a brief introduction, I told about my intention to record the conversation on a portable cassette recorder. Gijs responded enthusiastically, especially when I put a sticker sheet and some pens under his nose to draw a label to put on the cassette tape. REACT began immediately, and this was our conversation.

“The name REACT is a combination of letters that are fine for tagging. In terms of lettering, the R the E and A are cool to make. Nice sound too. And the meaning of course: 'react'. That's how I came up with it.”

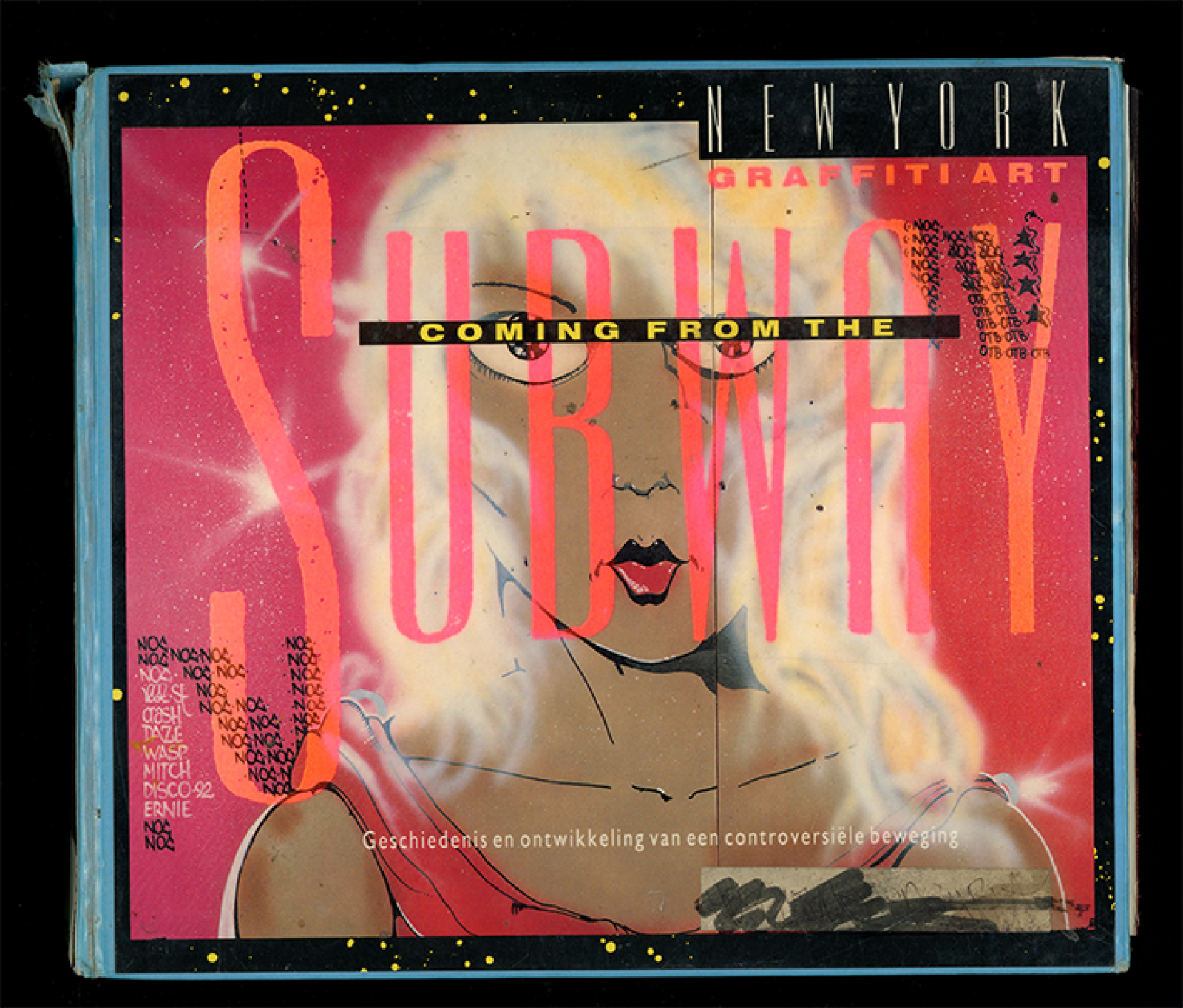

It's good that the graffiti scene in Groningen is getting attention. It is well deserved, especially what was made in the early '80s and '90s. In 1983, Frank Haks, together with the Boijmans van Beuningen, brought the world's first graffiti exhibition in a museum atmosphere via Rotterdam to the Groninger Museum; “Graffiti, Ten Writers from New York.’’ A few years later, in 1992, Frans Haks, Henk Pijnenburg, Poul ter Hofstede and Froukje Hoekstra organized the follow-up exhibition '’Coming from the Subway, New York Graffiti Art'’. Both exhibitions had a groundbreaking influence on hip-hop and graffiti culture in Groningen. Big names from New York, such as Dondi White, Quik, and Futura2000 participated and inspired Gijs and his crew.

The question often arises as to whether graffiti belongs in the museum and whether the art form is not being beaten to death by taking it from the street to the canvas. But I think of the punchline by Grand Puba on Brand Nubian's “Dedication” (1990) that, for me, holds the answer: “What more could I say? I wouldn't be here today if the old school didn't pave the way.”

In addition to the graffiti exhibitions at the Groninger Museum, Gijs drew inspiration from the booklets of Vaughn Bodé, an American cartoonist and illustrator known for his comic-like reptile “Cheech Wizard’’. Through his aunt, who lived in New York at the time, Gijs obtained a few new copies, in addition to the booklet already circulating in his group of friends. These booklets were copied frequently, both with a copier and by tracing.

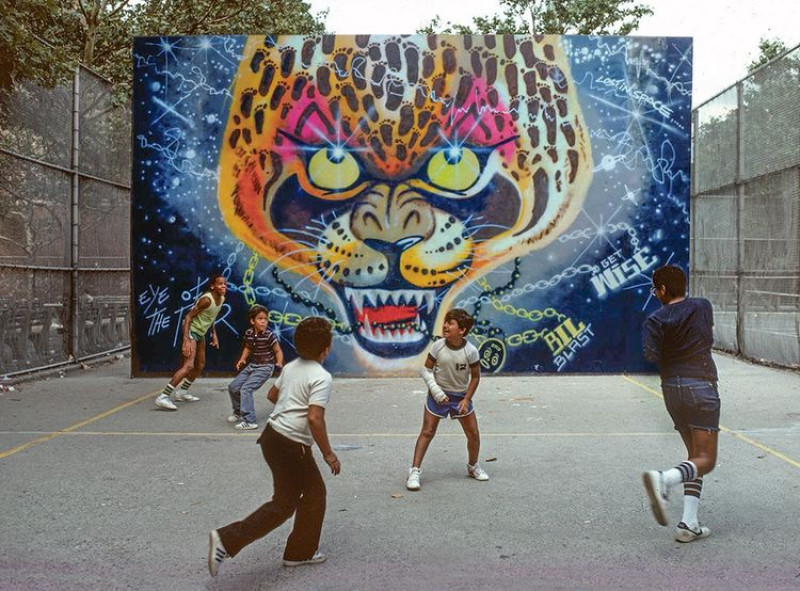

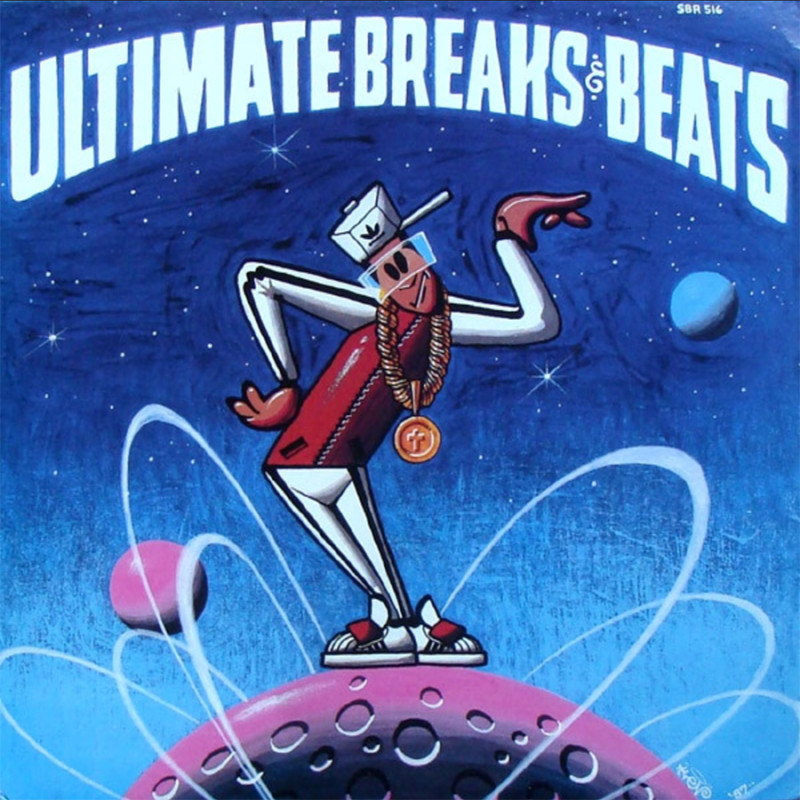

Recreating hip-hop records (such as Schoolly D's album covers and the compilation series Ultimate Breaks & Beats) and studying music videos were also a source of inspiration. Especially the tiger in the music video “Hey You” by The Rock Steady Crew (1983) made a big impression.

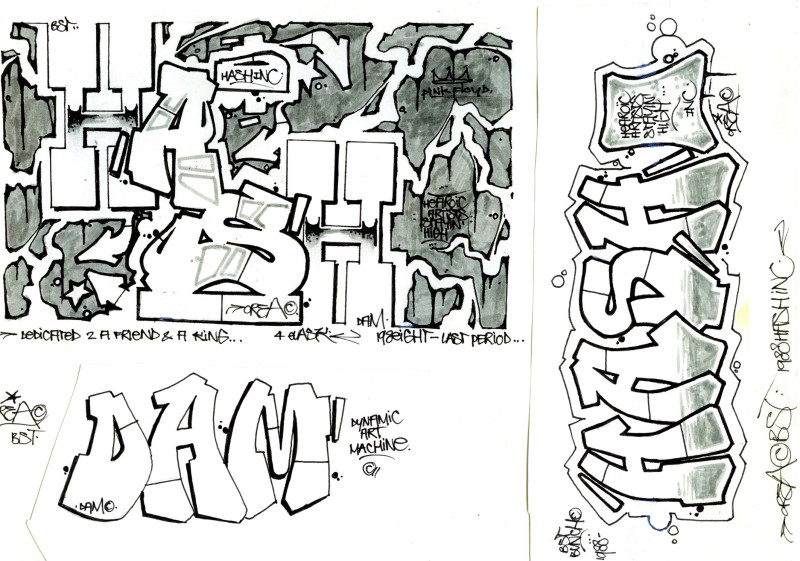

Gijs’ and his friends’, ROY and OREA, favorite pastimes were a combination of drawing, listening to hip-hop and smoking joints. Together they formed the crew HASH Inc. by ROY & OREA around 1987 and short for Heroic Artists Staying High, referring to the striving to be the best and smoking joints. While his friends focused on letters, REACT was mostly drawing “puppets” and exploring “wacky shit'’ like a foot with smoke out of it.

“Lettering is always subject to fashion. So you had this 'Wild Style' and there had to be all these arrows in it. I also looked a lot at posters from the sixties with that psychedelic lettering.”

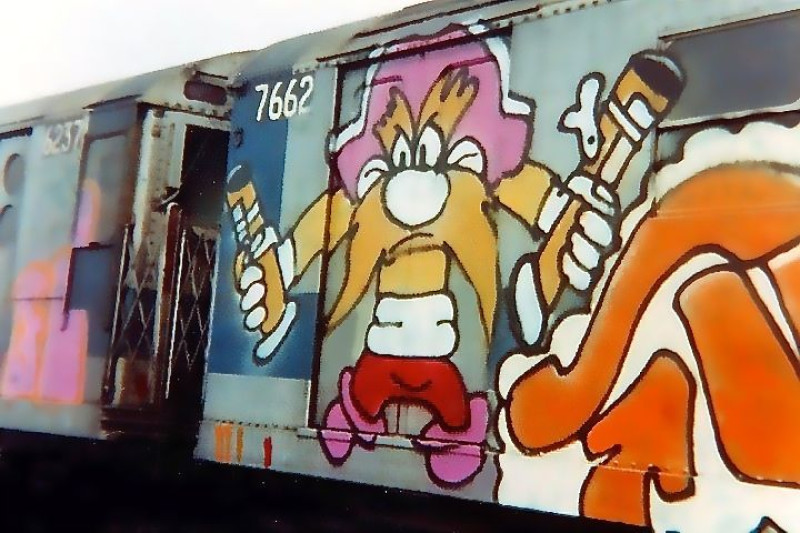

In the book Coming from the Subway, New York Graffiti Art, I learned about the origins of subway graffiti in New York. Starting in mid-1974, cartoon characters appeared en masse on trains, including “YOSEMITE SAM” from TRACY 168. A fun detail is that graffiti writers from those days often stuck their street number behind their name to represent their home street and expand their territory. Despite these hints, the police rarely succeeded in tracking down the writers. REACT was never caught, except for that one time at school when the teachers saw a link between the drawings in his diary and the ones on the school building. He immediately had a bottle of thinner shoved into his hand to clean everything up. Practicing during drawing sessions and then enlarging it on the street was the ultimate kick for Gijs. “Then it's right there. The next day you cycle past it and it's still there.”

“Every form of art starts with endless imitation, practice, practice, practice. And if you can do it, then see if you can color outside the lines.”

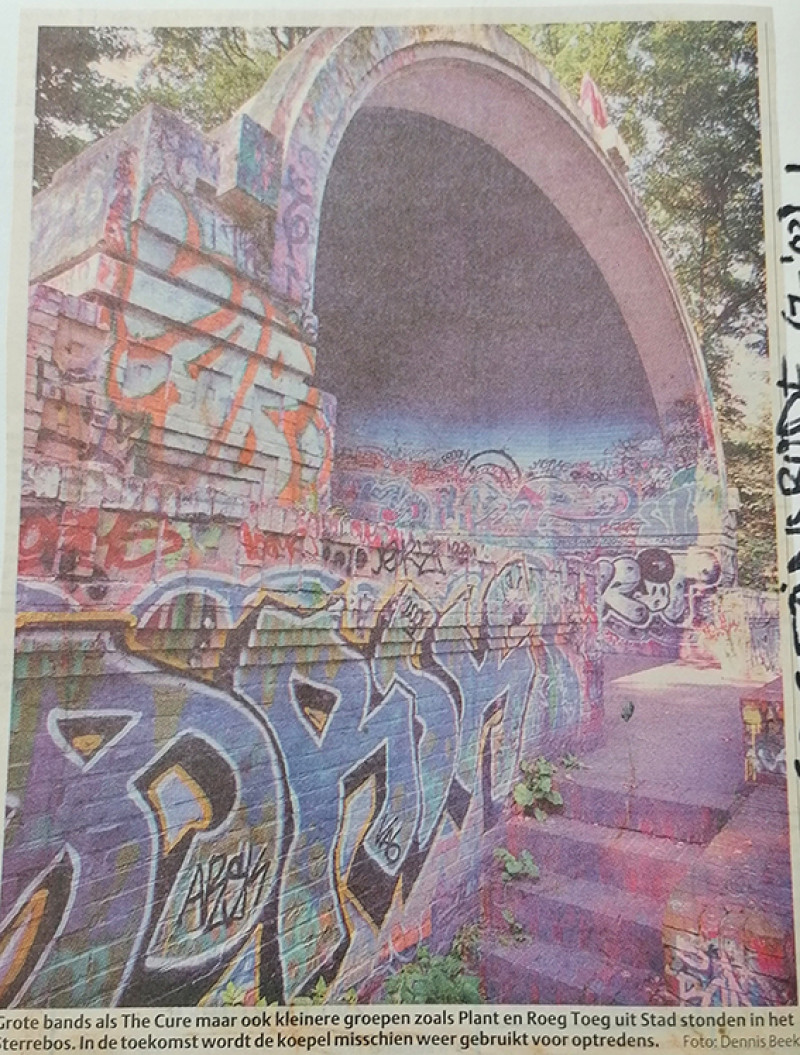

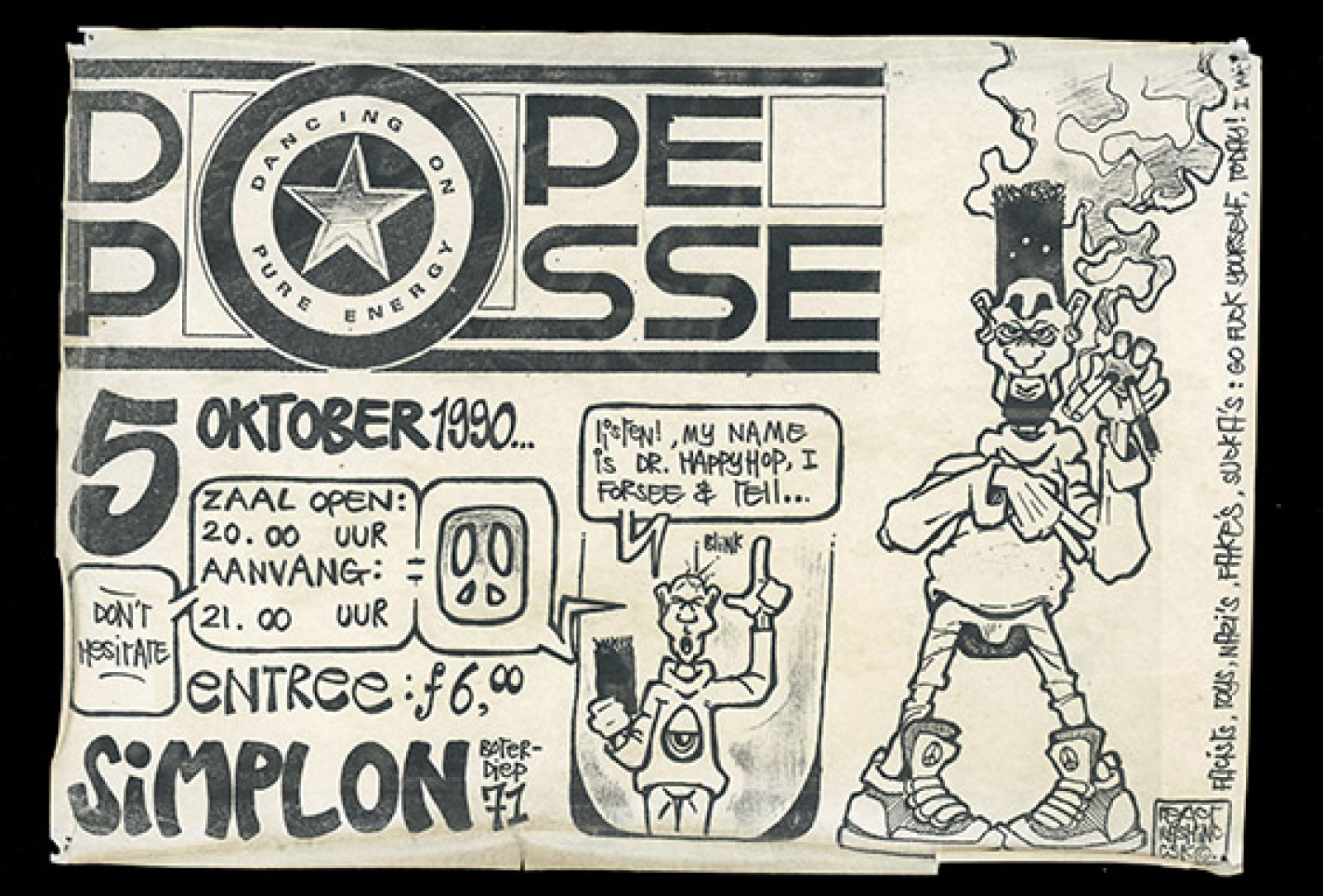

One of Gijs’ greatest prides is the “dome piece” in the Star Forest. “A nice spot, that's where your work could really pop.” A “burn” represents a nice piece, and a “burn up” refers to the burning up joints. “Joints and drawing go well together anyway. Nice tunneling,” says Gijs. “The dome piece contains several references, such as 'Let it grow' Tthe Jonko's) and 'Goodbye Cab,' a message to a good friend who left for Curaçao.” Friendship was the guiding principle, and Groningen had a close-knit hip-hop community at the time. “Groningen was pretty much a rock town, so we set ourselves against that.” Poppodium Simplon was an important meeting place and booked cool gigs such as Dope Posse, 24K and Da Zombi Squad. Gijs became part of Da Zombi Squad, the most notorious and successful underground hip-hop formation of Groningen. “I didn't make beats or rhymes, no, I drew. Posters and CD covers were drawn by hand, because there were no computers back then. Making a mistake meant -shit! - start all over again.”

Aside from drawing for Zombi Squad, Gijs worked behind the bar and drew posters for Simplon, and he was active as a volunteer at Simplon's screen printing shop. “Just because it was cool. I got some tokens and free tickets to gigs. It was of a different level to see your posters scattered across record stores and through the city.”

He continues: “We used to get spray cans at the Kwantum. Black car paint. That was pricey for an adolescent without much money, so occasionally a canister would disappear from the store...” “...Or we'd get cans in Amsterdam, but that didn't always go unnoticed. Those Amsterdam people would be waiting for you around the corner with a choice: turn yourself in or get beaten up. You could also get ripped off at the stalls on Waterlooplein...” “There was always rivalry between the North and the Randstad; everyone wanted to be the best. Kees de Koning (Top Notch, Amsterdam), for example, would sometimes ‘downplay’ Da Zombi Squad to push his own list forward - a form of cockiness.”

Gijs made a foray into house and acid-house between 1990-1994/95. “That was a vague blur for me.” He painted bright canvases that lit up under blacklights, but always in contact with hip-hop. Graffiti took a quieter form in Gijs' life over time. “All the shutters were done by now, and as you get older, you set other priorities. You have to put bread on the table and that 'die-hard' feeling dilutes.” With pride, Gijs tells us that he was able to turn his hobby into his job and will never stop drawing.

Sometimes, on a wacky night with his friends, they'll go out again with a spray can. Or when his little son has built a cardboard house, it, of course, has to be tagged. Gijs lacks at times the open-mindedness of those days and the fact that everything was new. “Hip-hop was new. Breakdance was new. The creative kick was new. Great times.” It felt like we could have chatted there all day, but the cassette tape was getting full and Gijs had to move on to his next appointment. I thanked Gijs for his time, the great stories and the nice meeting. He carefully stuck the drawn-on cassette labels on the tape and we said goodbye. You can still spot a real REACT tag, but the chances are slim. “It's kind of part of it; it has to disappear,” says Gijs.

On the basis of our conversation, I picked up two CDs featuring Da Zombi Squad. Although I was already familiar with this legendary crew from the far north, I was extra excited when I discovered that Gijs was part of this hip-hop formation. I listened to Exiles From Da Neverlands (1992) and the '95 remix of “Crazywild” on Beats & Bedrocks vs. Art. (released in 1995 by Studio Boterdiep on the occasion of the protest against strict municipal noise standards). At that point, I only wanted one more thing: to go back to the early nineties with Da Zombi Squad, eager emcee's, scratching subway lines, thick black outlines, 'reptile-like puppets' and Quantum burners.

What was your role in the '80s related to graffiti (Artist, journalist...etc)?

'Being part of the crew as an artist, drawing and doing graffiti together.'

What was your (artist's) name?

'REACT'

Where were you active?

'Groningen, Groningen-Zuid mainly.'

What scene did you belong to?

'Hip-hop.'

What do you think is the purpose of graffiti?

'To express yourself, to give something positive to a gray wall.'

Why did you want to do graffiti in the first place?

'Just cool. Hip-hop from America. New. Just wanted that too.'

What makes(s) graffiti so appealing?

'Just cool. Art form with schwung. It has a lot of vibes. It's fun to see. Letters and figures in the right proportion. There is movement in it. Dynamic.

How did a graffiti writer gain prestige?

‘Making great pieces. Making pieces that others were talking about. In crazy places, even better.'

How did you show connection in the graffiti world?

'Respect for each other and each other's drawings. Reviewing and judging blackbooks. The scene where you drove each other forward. You didn't keep each other down, you had fights, but more like the battle that's in there, just like in breakdance. Making each other better. Pulling each other up.

What showed rivalry in the graffiti world?

'Crossties. Cycling by the next day, someone had gone over it. Copying and mimicking letters or characters.

Did the people around you know you were doing it?

'Yes. I was open about it, to friends and close ones. It was cool, too, of course. But you didn't tell a teacher, of course, because then they knew who had done it and other writers knew who was who.

How did people around you feel about your activities?

'I think a lot of people didn't understand. People were more respectful, I think, of what they saw as 'Oh, that's a beautiful mural'. The art-form of 'I wrote my name everywhere'. 'Yeah, for most people it didn’t make so much sense.'

How did you think society viewed it?

'The social acceptance of graffiti began, of course, because museums and leading galleries started showing it. They began to take it seriously as an art form and, with it, the appreciation for the graffiti artist also grew. But that took a long time.

Are there any specific places in Groningen that symbolize your graffiti days for you?

'The dome in the Star Forest and the Hall of Fame at the old brick factory.'

Why did you eventually stop doing graffiti?

'I still draw. You go to work, you get older, you have to make money, you have to get a job. You want to make a living with your creativity. I still draw. I never stopped, just not on the Wall.'

How did your time with graffiti affect your current life?

'In that I still get inspired by the way I look at things. The way you look at forms continues to influence you for the rest of your life. And that in itself is good. I feel very connected to hip-hop, b-boying, rap and graffiti. But that's broader than just graffiti.

What did you learn from it?

(REACT thinks for a moment and responds) 'Yeah.... A kind of camaraderie, in a way. Not giving up, to keep going, wanting to do it a little better each time.'