Sex and French Fries

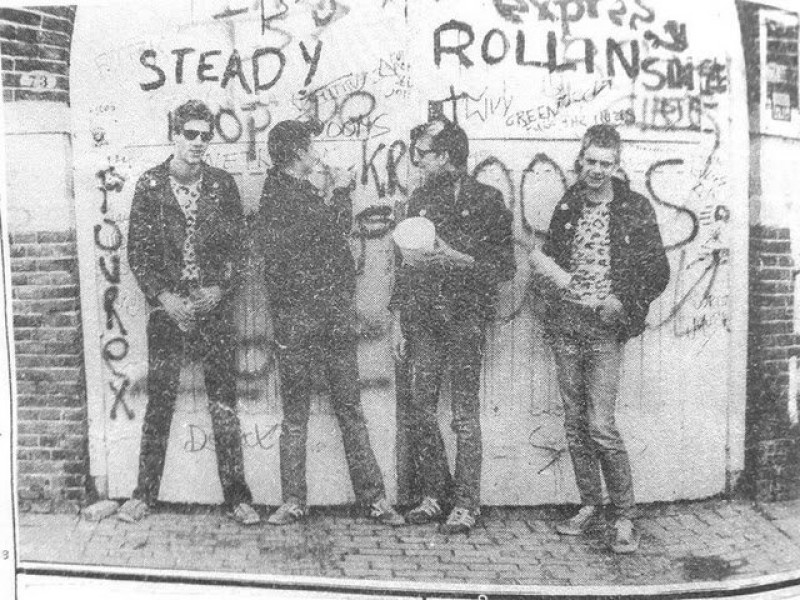

In the early 1980s, life was bleak. The economy was struggling and unemployment was on the rise. You can see it everywhere, not excluding the streets of Groningen. The city had a toughness to it with many buildings rundown and boarded up. Everywhere you looked, you saw graffiti: On walls and buildings, full of little drawings, funny remarks and obscure band names. City dwellers were fed up with the ‘’mess’’ in public spaces.

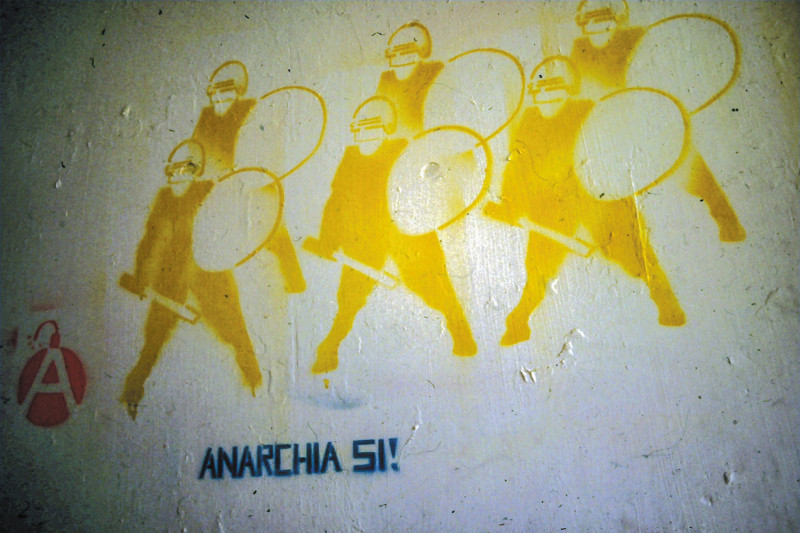

What city dwellers and shopkeepers see as an ugly mess is, for its creators, not only a source of entertainment, but above all, a way to make themselves heard. With graffiti and punk, young people in the early 1980s resisted bourgeois society, when everything seemed to be getting worse and worse.

The primal scream of punk

Punk began as musical, primal screams, in the second half of the 1970s. As a reaction against music that had become far too neat, far too complicated and, above all, far too commercial, bands deliberately started playing loud, short and fierce songs. Away with those long solos and complicated concepts: Punk is going back to the essence. If you need more than three chords and two minutes, it's not worth it. The cry “No Future!” expresses not only resistance and revulsion, but also the powerlessness that the youth experienced in the face of bourgeois life and about the prospects for their own future. For a job, a home and a secure life seemed to become increasingly unattainable.

This is how punk became a lifestyle, characterized by doing things yourself, sharing with others and protesting against everything bourgeois. Increasingly, punks set themselves apart with distinctive looks: Mohawks, safety pins used as jewelry and leather jackets with metallic studs. Prompted by the dire economic times, squatting was on the rise: After all, the chance of owning one's own home was minimal.

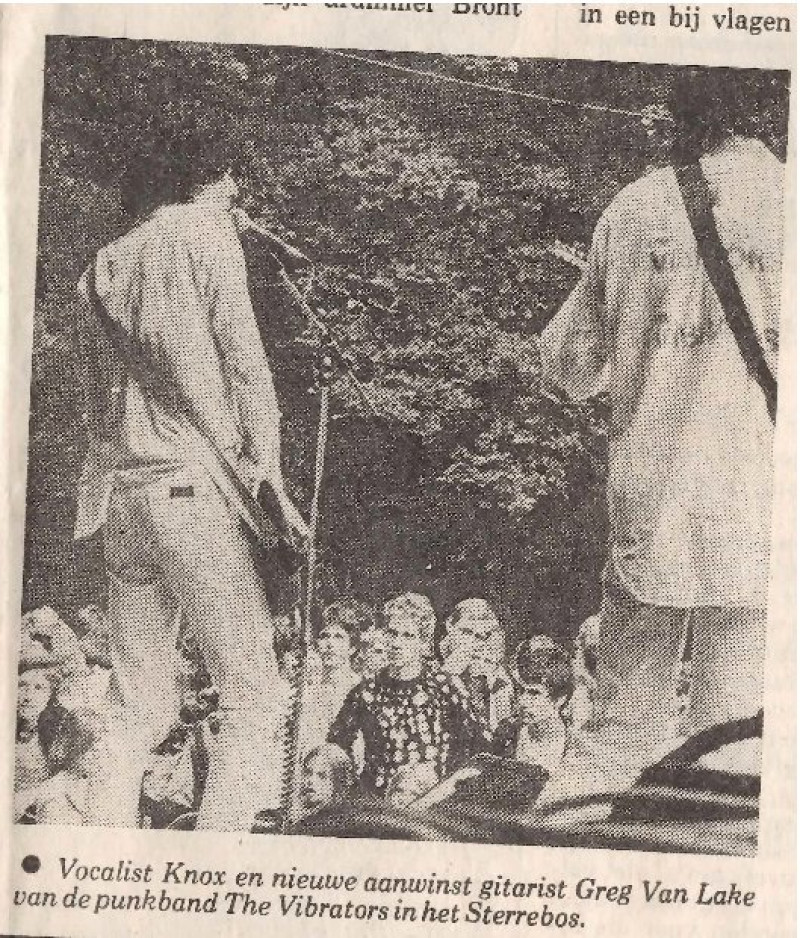

As a music genre, punk was both embraced and declared dead within a few years, much to the annoyance of the people who got more out of it than delusions and release. To them, punk stood for an alternative and genuine way of life, as possibly detached from social conventions and the laws of commerce. For the youth of Groningen, this contrarian attitude and lifestyle had a particularly attractive quality. Towards the end of the 70s, at concerts held in the Sterrebos, many young people made their first acquaintances with punk. In the rebellious music and the strikingly dressed fans, they experienced absolute freedom.

Into town with felt-tip pen

An inseparable part of punk identity remains music. The old RKZ squatted and grew into a rehearsal space, where countless young people started their own punk bands. Simplon became the place to be: Not just because concerts were held there, but also because fanzines were made in the room upstairs. On the stencil machine of Simplon, young punks printed their own magazines, in which bands and other developments were discussed.

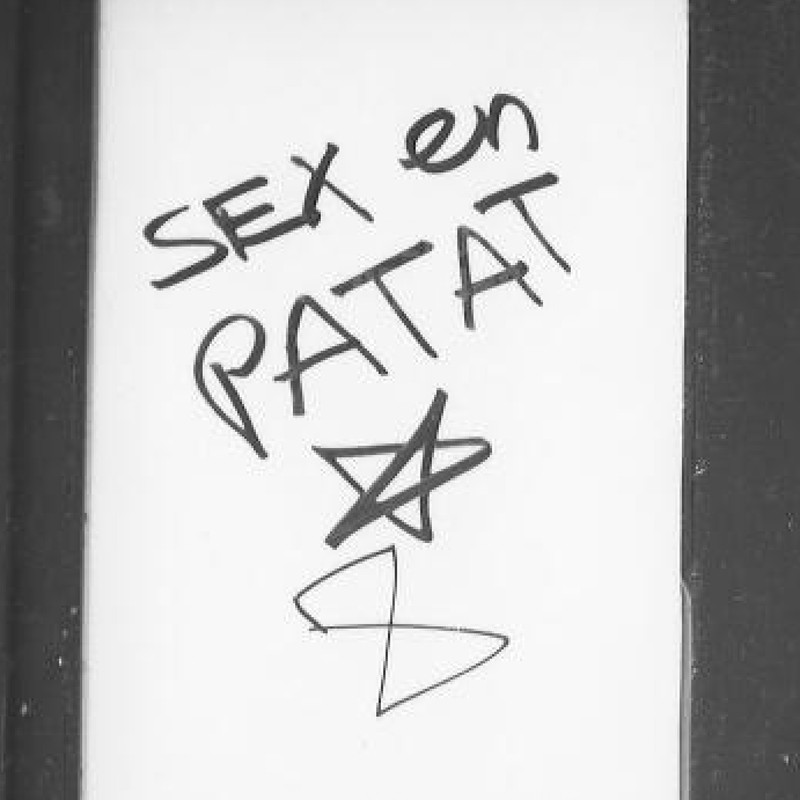

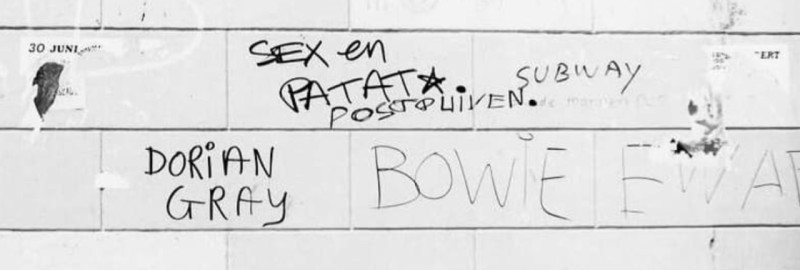

The primary way to communicate and shout out new bands to each other was even simpler. In the early 1980s, armed with felt-tip pens and spray-paint cans, punks would head into town. Everywhere they could, they wrote their favorite band names or their own nicknames. In this way, they covered the whole city with striking names, funny slogans and little drawings. Shoppers would wonder who Slonz is, whose name seemed to be on every wall. People would raise their eyebrows at the slogan “Sex and fries” and were taken aback by band names like The Boobs and Vomit Trays.

“During Stars in the Forest at the end of the 1970s, many young people were introduced to punk for the first time”

Messing around at the town hall

Opposite Café Josje (later De Ster, and now The Jack), on the Peperstraat, there is a white wall, near the courtyard and it was one of the preferred spots to write band names or any other message. Other young punks would pick out the messages and respond, unknowingly creating a precursor to a group app or message board. There were several places downtown where punks were busy with their felt-tip pens: The phone booths at the start of the Herestraat were popular, and those who really wanted to make an impression would venture onto the walls of the city hall. Of course, not without risk. Many city residents were not happily waiting for groups of Teenagers to smear the public space. It was always necessary to be on the lookout for patrolling officers, although an arrest and a small fine could have a status-enhancing effect in the right circles.

Later in the 1980s, the atmosphere in the city deteriorated. The hardcore ‘ultras’ of FC Groningen also began to concentrate in the city center, and they wanted nothing to do with the punks. Increasingly, violent confrontations arose between the two groups.

Why art?

Meanwhile, graffiti as a form of expression was also changing. In New York, where it originated as part of street culture, it grew into an art form, and with it, creators developed into artists. The Groninger Museum was among the first museums to recognize this and to organize exhibitions to display it. Groningen's Mick La Rock (Aileen Middel) played an important role in the recognition of graffiti as an art form. As a graffiti artist, but also as a writer and curator, she constantly demonstrated the artistic value of graffiti.

Most Groningen punks, however, look at it all with a shrug. Why call it art? Their graffiti (barring exceptions) was not about that at all. It was nothing more than itself, graffiti - a nice way to make contact and affirm one's identity. Why would you want to display that in a 'petty bourgeois and commercial museum'?

Whether they saw it as art or not, punks, with their felt-tip pens and spray cans, colored the Groningen’s streets during the 80s. You can still find the rapidly fading remnants if you know where and how to look. Beautiful or ugly, they most certainly are tangible reminders of a unique scene and of the social life of their time.